The open wooden boat with an outboard motor, moored under the Canje bridge at the confluence of the Berbice River, held just ten passengers close together on three wooden planks, 2-3-3, in addition to the captain and the guide sitting on the edge of the stern. We ranged in ages from about 20 to 70, mostly originating from Guyana with a couple from further afield. Excited about the expedition and wearing walking boots, rain gear and sporting water bottles in outside pockets of small day back-packs, we set off under heavy cloud cover for the 88km trip up river to Fort Nassau; the site of the year-long rebellion by enslaved peoples from 1763-1764.

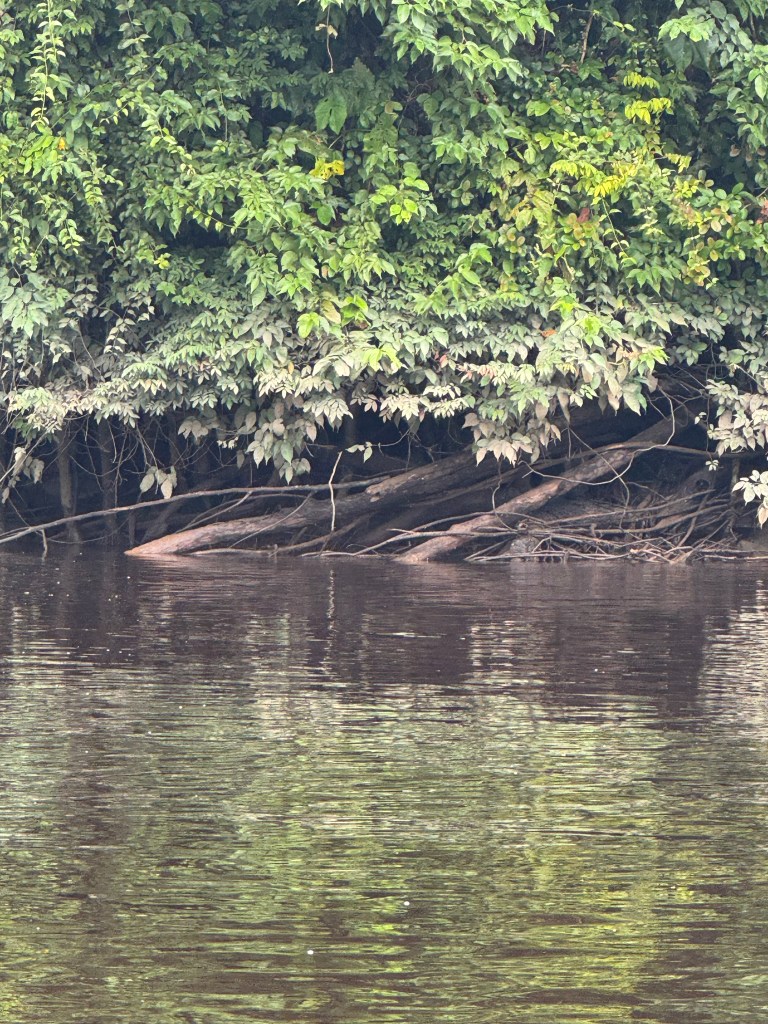

About an hour into the journey upriver, the rain began. Gently at first then a downpour with wind that swelled the river further, pummelled our necks and backs as we bent over to protect our faces from the needle-like shards of rain that soaked through to our underwear, made a mockery of our “waterproof” trousers, socks and shoes. The cool winds soon whipped up waves on the surface of the river which reached within centimetres of our knees, pressed against the sides of the small vessel that held us together as we bounced along the deep Berbice river, almost 595 kilometres long its dark, clear waters hiding names spoken softly along its banks and now, long forgotten, together with the children, women and men whose blood was shed in these waters over 250 years ago, under the long and brutal Dutch rule, and the shorter, equally cruel British colonisers.

Shielded, as if in the recovery position, arms around my head which was bent towards my knees, I envisioned the Dutch tall ships under sail or rowed by enslaved oarsmen navigating these brown/red waters. Relieved to be living in another century, in another time in history albeit with its own threats, our small craft slowed and turn into a wooden jetty, its steps sunk low into the river, white bubbles and clear spray, reminiscent of coca cola poured on ice in a tall glass.

My thoughts remained firmly with my ancestors, grandmothers and grandfathers of my family, perhaps hailed from Angoy country that bordered the banks of the wide Congo River, now The Republic of the Congo, but perhaps not… The name, like so many others has been renamed, un-named, disappeared, covered up, destroyed, discarded, undone. Who knows? The indigenous names spoken by other tongues have been misspelled, mispronounced, renamed and/or forgotten over time. The peoples who navigated these waters, the radar for the Europeans, no longer exist as they did 300 years ago and we now experience a new form of colonisation under new names; Exxon-Mobil, Chevron, Anadarko Petroleum and Occidental Petroleum.

The dense, almost impenetrable jungle inwards from the river, is separated in parts by paths made centuries ago, but overgrown and competing against the undergrowth that wants to cover up the past, our history. Coloniser’s, lay buried under the encroached forest and those that remain are engraved in Old Dutch, some with their crests and others have slid into the mangrove swamps that flank the old Berbice River and continue to penetrate the heavy clay soil. Every edifice; every church, town hall, court house, merchant’s house, assembly hall, soldiers mess, officer’s smoking room, every single one was built by the enslaved peoples of the Dutch East India Company; those who were shipped across the Atlantic and others, the indigenous peoples of the Guianas. Only a few bricks remain and some fewer grave stones, everything else has been reclaimed into the land by nature. The slave masters, merchants, priests and vagabonds that came to these shores in search of wealth both on land and below ground; timber, gold, silver and precious gemstones, together with the harvests of sugar, cotton, coffee and indigo have now left. As we walked for two hours in single file through dense undergrowth, following paths cut through the forest and into clearings, the intense heat and humidity unsettled my mind and body. I no longer feel at ease in this climate yet I am drawn to the land, the rivers, to the people and to a place I call home.

I went in search of the Angoys in Berbice, the birth place my father and grandfather and perhaps my great-grandfather, my grandmother and maybe my great-grandmother. Who knows where I hailed from centuries ago. What are the names that run through my blood and in my DNA. Where do I come from and what’s in a name? These questions, and many more, remained unanswered on this journey.

(All images taken by the author)

Thank you Sisi.

I find that names carry a lot of meaning based on the person, the name and circumstances. I need to start researching my own sur-name Pefile. No one in Eswatini has that name and very few SA’s have it. This says to me that it was chosen by my grandfather, great grandfather or great, great grandfather.

A thought-provoking piece.

Regards

Sibongile

LikeLike

I’m so happy, Siri, that you too will seek out the origin story to your own name. For us, on the other side of the Atlantic, there are so many layers of theft that obscures, hides, changes and obliterates our past. It now remains my quest. Thank you so much for reading, and commenting on this post.

LikeLike

[“needle-like shards of rain that soaked through to our underwear, made a mockery of our “waterproof” trousers, socks and shoes”]. These images are so vivid that a reader comes with you on this set-discovery journey. Fascinating how you incorporated humor, is it not powerful how a prolific writer can lighten up reader’s mood in what is clearly a difficult topic. You are incredible Patricia!

[“like so many others has been renamed, un-named, disappeared, covered up, destroyed, discarded, undone]. This is so profound—yes, discarded because they do not see any ‘use’, covered up because they are scared of truth. From the images to your vivid description of your possible home—Congo, you have done that with unmatched prowess. What is in a name? Whose blood run through your veins? and what does that say about you as a descendant who is piecing together a puzzle, without enough data because it was discarded. Without artifacts because they were deemed unworthy. Yet the same land and water you are crossing is forever stained with their blood, sweat, elegies and hope, and longing! Thank you very much for sharing this Patricia!

LikeLike

Francisco, you know only too well what it means to have a name and yet the place has been removed. Belonging somewhere is obscured in paperwork and ignorance. Thank you for reading so keenly into my writing and for then sharing your thoughts with the world. I am deeply grateful

LikeLike

What a well written piece!

LikeLike

What a well written piece!

I felt myself being drawn in and wanting more. A sign of an outstanding author!

Well done my dear cousin.

LikeLike

Dear Anne, so glad you enjoyed the read. It was a great trip.

LikeLike

Once again, your writing got me thinking about the history of my own land, my own ancestors under the same colonizers. So many stories, so many names got lost in those times, as if they didn’t matter, our ancestors. As if they were inanimate objects, just like the wealth the colonizers dug out from our land–maybe even less valuable than the gold, timber, and all. And then I’m filled with feelings I can’t comprehend–anger? Sadness? Hate? Sorrow? Grief? And whose feelings are these, actually?

LikeLike

For me, Anastha, it’s all of those; anger, sadness, hate, sorrow, grief … and many more. We are linked through colonisation across so many, many lands, people and places. Now, it’s a new kind of colonisation that has set into this 21st century and our wealth is still being extracted. Our two countries, Indonesia and Guyana are also homes to some of the last pristine rainforests. The connections continue …

LikeLike